Mapping Memory Landscapes in nodegoat, the Indonesian killings of 1965-66

CORE Adminnodegoat is developed as a collaborative research environment that supports participatory research projects. To test its ability to combine various participatory roles with its ability to digest complex and heterogeneous data, we spent two weeks in Semarang, Indonesia working with a group of students to reveal an infrastructure of violence. These students interviewed survivors of state-sanctioned violence and entered the information they gathered directly into nodegoat. Based on these interviews, the students visited a number of sites and interviewed people who lived or worked on these sites. As the data came from personal accounts only, the visualisations that are produced in nodegoat can be characterised as memory landscapes. In this blog post we will describe both the process and the methodology of this project.

The Dutch Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (NIOD) has set up a cooperation with the Universitas Katolik Soegijapranata (UNIKA) in Semarang, Indonesia that aims to address the anti-communist/leftist violence of 1965-66 in Semarang and the following years. The project that has emerged from this cooperation, ‘Memory Landscapes and the Regime Change of 1965-66 in Semarang’, is led by dr. Martijn Eickhoff (NIOD) and has resulted in two workshops at the UNIKA University in Semarang organised by Donny Danardono. The first workshop took place in January 2013, the second workshop was held in June 2014. During these two workshops students from UNIKA collected data on anti-communist/leftist violence by combining oral history and anthropological site research. The data includes relations between people as well as locations connected to the events of 1965 and the following years (e.g. places of mob violence, temporary detention, interrogation, torture, murder and mass burial).

Historical Background

The project focuses on events starting in 1965 during which outbursts of violence led to the killing of approximately half a million people in Indonesia. The historian Robert Cribb has argued that these acts of violence were carried out by anti-communist army units and civilian vigilantes. The motivation of this violence was an alleged communist coup d'état in Jakarta on the first of October 1965. Although the manner in which the killings were carried out varied greatly per region, a recurring pattern was the arrival of anti-communist troops from outside. Not only members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) were considered a target, also people associated with leftist organisations and people of Chinese origin were targeted.

The historian Baskara T. Wardaya has stated in his foreword to his bundle ‘The Truth will Out’ that these events were subsequently formed into an official narrative by the New Order government led by general Suharto. In this narrative, the coup d'état was portrayed as a violent killing of seven military generals by the ‘Thirtieth of September Movement’ which was led by the PKI. According to this narrative, the corpses of the generals were mutilated by a group of women who were members of the Indonesian Women’s Organisation (GERWANI). As a result of these cruel and barbaric acts, the people of Indonesia attacked PKI-members as an act of revenge. This mass murder was sanctioned by the principle of ‘kill or be killed’. After these killings, the regime continued to arrest and imprison PKI-members without trial as they were seen as state ‘traitors’. Once released, these people were still regarded as dangerous and given special labels like ET (Eks Tapol, ex political prisoner). After the fall of the New Order in 1998, this official narrative has not been contested. The documentary ‘The Act of Killing’ by Joshua Oppenheimer shows how the perpetrators have never been held accountable for their involvement.

In this context, we asked survivors of these events (who identified themselves as Eks Tapol) to share their experiences of anti-communist/leftist violence with us. We explained that students would interview them, that we would record these interviews and that we would store the data gathered during these interviews in an online research environment. Most of the survivors were pleased that their stories were being heard and that this was done in an intergenerational context (a majority of the students grew up with the idea that communists are extremely dangerous). Some of the survivors expressed their concern to share personal information with us. Especially seen the use of an online research environment, a traceable and rigid form of documentation.

We reassured the survivors that we would store the material safely and not share the data with anyone outside our project. Survivors could opt for an alias to be used instead of their real names. Anything that would be shown to a larger audience would be done so in an anonymised format.

All these local parameters are of great importance for the setup of the project. As the official narrative completely neglects the fate of the victims, the only sources available are the people who have actually experienced these crimes. Moreover, due to the ongoing political sensitivity, especially as the workshop took place during the presidential elections of 2014, we had to maintain a low profile and keep the project small in scale. The resulting collaborative and participatory process was therefore for a large part a necessity. The project setup in itself became part of the research process. The questions we wanted to answer in the course of the project focused both on the digital representation of individual and collective memory as well as on the participatory design of the project and data entry processes. In this sense, our collaborative approach was in effect a hybrid form of two modes of collaboration in the humanities, as described by Lisa Spiro (PDF). Although we were building a digital collection of sources, we did so in a participatory online environment.

Workshops

During the first workshop in January 2013, a group of 10 survivors were interviewed. After examination of these interviews, a relation in time and space between instances of violence was evident. The comprehensive range of entities that were named in the interviews can be connected to each other by their shared identification, their co-occurrence, or their movement through space (e.g. people were being detained in a shared time frame, multiple persons could be linked to the same detention center, or multiple interviews mentioned the same mass grave).

The second workshop took place in June 2014 at the UNIKA University in Semarang. Here we set out to integrate a networked approach by collecting and entering information gathered from 15 new interviews and additional site research directly into nodegoat. This meant that the 10 students of the master programme Environmental and Urban Studies (PMLP) who conducted the interviews had to get a basic understanding of how relational data models function and how they could apply this knowledge to nodegoat.

During the first days of the workshops we trained the students in working with nodegoat. As they would mainly be gathering biographical data, their first task was to enter their own biographies into nodegoat. To achieve this, they had to work with three Types: ‘person’, ‘institution’ and ‘city’. A new Object in the Type 'person' had to be given the Sub-Objects ‘birth’ and ‘education’, a new Object in the Type ‘institution’ or ‘city’ had to be given the Sub-Object ‘location’. See the nodegoat FAQ for an elaborate explanation of these terms. This exercise showed them the process of creating new objects for each entity that they would encounter (e.g. persons, schools, sites) and how these could be related to each other (e.g. a person relates to a school via an education). Moreover, as all these objects have different dates and relate to numerous locations (e.g. the birth of a person relates to a city and this city has latitude and longitude values specified), they immediately saw how a personal biography can be plotted on a map and visualised through time.

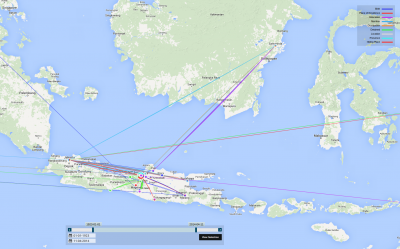

As nodegoat is a collaborative online research environment, the students were able to enter their data in one dataset. The product of this task resulted in an interactive map showing an overall migration towards Semarang that includes all the birth locations of the students and the schools they have attended.

Methodology

The data gathering process is outlined by the object-oriented methodology of nodegoat. This methodology asks researchers to transform each entity they encounter (e.g. humans and non-humans; events and emotions) into an object and to describe every relation and association of this object. To do so, an environment is needed that stores and analyses the object, its relations and associations. nodegoat provides this environment and allows researchers to define and continuously update the data model they need to process their heterogenous objects.

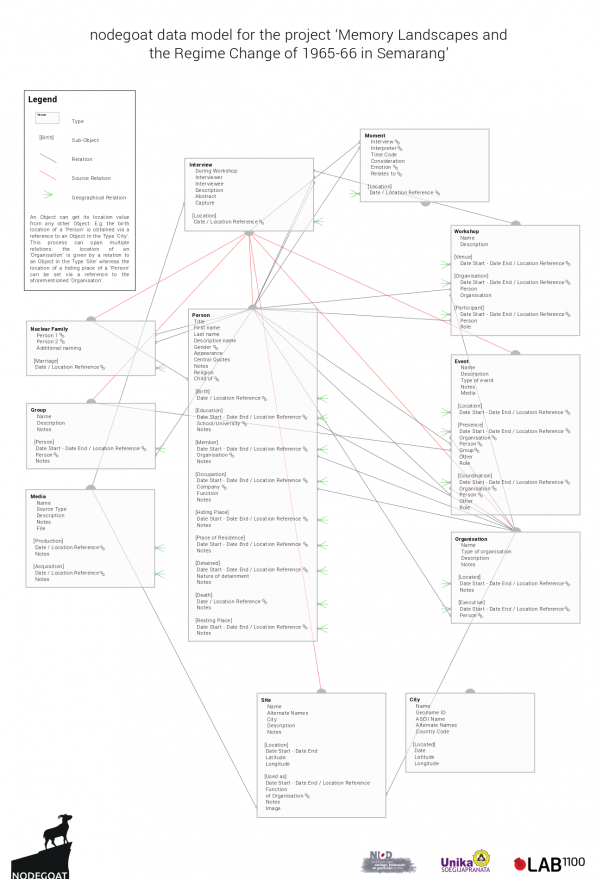

For this project we defined eight Types in which objects were stored: ‘workshop’, ‘interview’, ‘person’, ‘organisation’, ‘site’, ‘event’, ‘nuclear family’ and ‘group’. In the course of the workshop, a new Type ‘moment’ was proposed by workshop participants and added to our data model. The Types ‘workshop’ and ‘interview’ could be seen as redundant as they contain objects that could have been stored in the Type ‘event’. We opted to maintain these Types for processual reasons as the current structure would be more accessible for workshop participants. Each object is defined by a dynamic number of Object Descriptions and a dynamic number of Sub-Objects (see figure 1 for an overview of the complete data model). Each bit of information is stored only once; namely in the object of which it describes an intrinsic aspect. All the information is subsequently connected by means of relations and associations. Relations describe intrinsic aspects of the object (interviewee, organiser, etc) whereas associations reveal the circumstances of the object related to other objects (member of an organisation, presence during an event, etc).

This methodology is closely connected to actor-network theory (ANT). nodegoat aims to provide researchers with an environment that allows them to bring the ideas associated with ANT into practice. The combination of tools and methodology offered by nodegoat distinguishes three levels brought together in an assemblage of objects: (1) the identification of all objects and their own possible definitions, relations and associations (cross-referencing); (2) the identification of all (contradictory) definitions, relations and associations related to each object (cross-referenced); (3) the identification of objects that are associated relationally, in space and in time. The outcome of this process creates a dataset that not only includes objects that function as hubs or brokers, but also objects that are situated in the periphery of the network. Each object has their controversies and conflicting perspectives mapped, revealing their full complexity. The final result establishes the contextuality in which the objects are to be approached. Within this context, each object functions as a starting point for the exploration of the complete dataset. As identified by Annemarie Mol (PDF), this process allows for a continuous shift of perspectives, producing a multitude of different renderings based on the body of data.

This inherently dynamic data model and output connects to the elastic nature of our sources. As we solely rely on individual accounts based on personal memory we have to deal with a great variety of content, perspectives and reliability. Since these sources form the basis of all the data we work with, we acknowledge this diversity and regard each bit of information gathered during the interview sessions as equally relevant. In a next project, we aim to explore how this process relates to the concept of a collective memory as described by Maurice Halbwachs (since an official narrative lacks, this could produce valuable new insights). Due to our object-oriented approach, we would be able to employ a rhizomatic analysis of knots of memory, as was suggested by Michael Rothberg in his recent critique of Nora’s Lieux de mémoire (PDF).

Gathering Data

The interviews were conducted at the homes of the survivors. Groups of students and academic staff recorded the interviews with a camera and took notes. As the project aims to expose a memory landscape, the interviewers did not need to focus on establishing ‘facts’ mentioned by the interviewee but to record an account based on the personal memory of the survivor.

The process of data collection resulted in a complex and heterogeneous dataset; the data varies from information on places of birth to eventful stories about personal experiences during a transport of detainees. We first set out to make one object for each interview within the Type ‘interview’. This object is used as source reference for any input that would be made based on information from this interview. Secondly, we entered the basic biographical data of the interviewees. Thirdly, all the places of detainment of the interviewees were included in the objects of the interviewees. As all the data was entered into one environment, the accumulated data immediately gives us a comprehensive overview of all the persons, institutes and locations that were mentioned in the separate interviews.

A challenge we faced during the data entry process regarded the definition of similar locations mentioned throughout the interviews. Sites that functioned as detainment centers were used for different purposes before 1965 (e.g. as a school), and again had various functions after 1966 (e.g. community building or shopping mall). This means that the names and descriptions used to identify one location vary greatly. As all the data was entered in a shared environment, decisions had to be made collectively whether we were dealing with one location or that we should differentiate between each identity. We opted to combine the identities for each location where possible with the purpose to also recreate a location's biography and context. The ability of nodegoat to immediately visualise a newly added location gave us instant feedback by showing us whether we were dealing with a new location or if a cluster of locations had emerged that needed to be analysed.

Next, a number of events that could be distilled from the interview (e.g. a meeting, demonstration or kidnapping) had to be identified. For this, the students had to make an object in the Type ‘event’, provide a description of the event, and provide the course of the event with the configuration of the attendees that were present (i.e. persons, groups). This proved to be a difficult task as the stories had to be broken down into separate events and can be modelled more freely.

After we had established a first overview of sites of violence in and around Semarang, the students visited a number of sites in order to conduct field research. During their field research, the students and research team interviewed people that lived or worked on the visited location. These interviews provided the project with new information relating to the landscape of violence.

At the end of the data entry process, students remarked that it was hard to store specific moments that could not be described as an event, but did contain valuable information about the interviewee during the interview itself. This extra information could relate to an emotional reaction, a non-verbal gesture or an expression of uncertainty connected to a statement in the interview. To accommodate this proposition, we created a new Type in nodegoat called ‘moment’ in which objects can be identified that describe considerations (with a relation to the interpreter) of the survivor and allows for the classification of these considerations by means of emotions. These moments can subsequently be used as a more specific source for instances originating from the interview.

This investigative approach of the workshop connects well with ANT as it encourages participation and the inclusion of all actors (of any kind). Participants, data and the documentation of the process are all shared within the same environment. In this process we think it is not desirable to group subject matter beforehand, or to exclude anything that comes up during the research process. Participants with varying backgrounds and focus are encouraged to actively involve themselves in both the design of the workshop as well as in the processing of the data at hand.

Outcomes

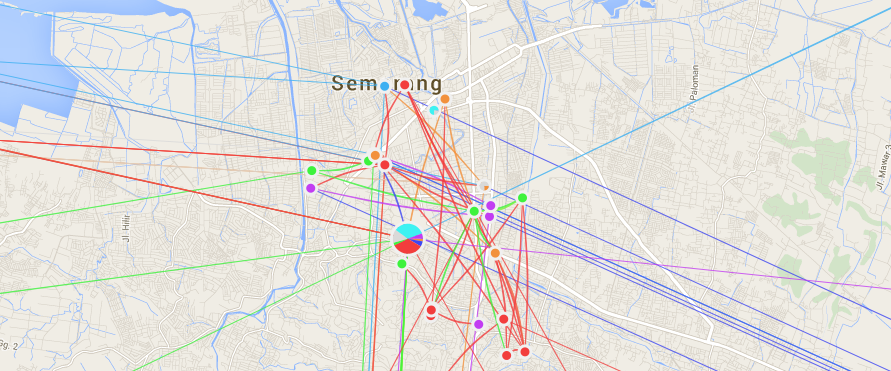

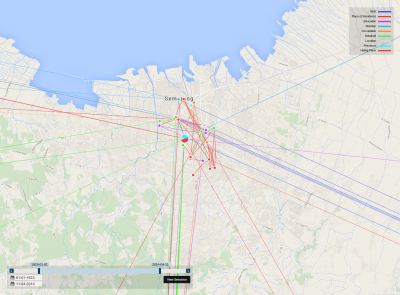

After two weeks of training, conducting interviews, visiting sites and entering data, our project in nodegoat now contains 20 interviews, 57 persons, 102 organisations, 36 sites, 24 events, 14 nuclear families, 3 groups and 2 moments. For the 57 persons, 302 Sub-Objects were specified ('birth', 'education', 'member', 'occupation', 'hiding place', 'place of residence', 'detained', 'death', 'resting place'). As a result of the object-oriented framework in nodegoat, all objects are considered equal and every object can be connected to any other object. Due to the connectedness of the data model (see figure 1) each object functions as a starting point for an exploration of the data. This allows for a continuous shift of perspectives while browsing through this digitally represented ‘collective memory’.

|  |

The assemblage of personal memories within nodegoat and the geographical visualisation of these memories produced a first (localised) visual representation of the anti-communist violence in 1965-66. As the narratives of the victims are suppressed within the state sanctioned depictions of these event, this in itself proved to be a valuable outcome. Moreover, the geographical analysis of the locations mapped in Semarang revealed a number of patterns that allowed the research team to formulate new research questions. The most prominent pattern was found in the composition of sites where survivors were interrogated and temporarily detained in one area of Semarang and the location of a number of camps in another area. The research team focused specifically on questions regarding the confiscation of property and typologies of prisons.

Conclusion

The workshop demonstrated that nodegoat is able to support a participatory research process that aims to gather, connect and analyse personal stories. The flexible data design, collaborative working environment and the availability to visualise and analyse data throughout the process provided the project with the necessary equipment. However, looking at the skills that are required to transform interviews into a relational data model, the timespan of the workshop seemed to be insufficient. Although we were able to realise a number of high valued outcomes, the process would benefit from a longer duration and extensive training opportunities to help participants fully grasp the possibilities of a relational data design.

Due to the sensitivity of the information that was gathered during this research process, it will not be possible to share all the outcomes of the workshop publically. Still, as the stories that have been gathered had never been stored and connected together, the final dataset of this workshop forms an important resource that is both persistent and actionable. Since there is no combined narrative in place on the killings and suffering around 1965, this project may function as a first step that enables a more inclusive approach in addressing this episode of Indonesian history.

On a more general note, the workshop has shown that an oral history research project does not necessarily need to end in a static end product (e.g. a collection of media files, an article or a book). The created actionable dataset is in itself open for scrutinisation or further contextualisation as a result of its non-hierarchical design. Our rhizomatic approach enables re-use and transcends debates on restrictions of content and constraints of research questions. By saving data structurally in a shared environment, a new data resource is created that can be used by scholars who wish to continue this research or who want to use this dataset as context for a new research project.

A condensed version of this blogpost has appeared in the proceedings of the workshop ‘Histoinformatics 2014’ at the 6th International Conference on Social Informatics, published by Springer Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS): http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15168-7_34

Cited works

Baskara T., Wardaya S.J., 'Hearing Silenced Voices. A Foreword', in: Baskara T., Wardaya S.J. ed., Truth Will Out. Indonesian Accounts of the 1965 Mass Violence XXII-XLIII, Victoria (2013).

Bree, P. van, Kessels, G., 'Trailblazing Metadata: a diachronic and spatial research platform for object-oriented analysis and visualisations', in: Cultural Research in the Context of Digital Humanities St Petersburg (2013).

Cribb, R., 'The Indonesian Massacres', in: S. Totten, W.S. Parsons and I.W. Charny eds., Century of Genocide. Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views 236-263, New York (1997).

Mol, A. 'Actor-Network Theory: sensitive terms and enduring tensions' Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 50, 253-269 (2010).

Rothberg, M., ‘Introduction: Between Memory and Memory: From Lieux de mémoire to Noeuds de mémoire’, Yale French Studies. Noeuds de mémoire: Multidirectional Memory in Postwar French and Francophone Culture 118/119, 3-12 (2010).

Spiro, L. ‘Computing and Communicating Knowledge: Collaborative Approaches to Digital Humanities Projects’, in: Collaborative Approaches to the Digital in English Studies, 44-82, Old Main Hill (2012).

Comments

Add Comment[...] Termutakhir Terkait Genosida 1965-1966) (sila simak artikel lainnya) simak juga Mapping MemoryLandscapes in nodegoat, the Indonesian killings of 1965-66 *** Nodegoat is developed as a collaborative research environment that supports [...]